Why do we need an architectural plan for the sound? On Clubs, Sound, and What's in Between - Chapter: B

- Tamir Barelia

- Feb 2

- 5 min read

Okay, so now that our working premise and compass are pointing in the right direction, where do we start? We start with the club, in its most physical sense.

What cannot be changed: the structure, the sizes, and the relationships between the sizes.

In other words, we will need to understand the structure at an architectural level.

If architectural plans are unavailable, we will create them by taking on-site measurements and physically inspecting the structure.

Why is the architectural shape of a building so important?

Firstly, because the dimensions themselves are important. For example, the distances between walls, ceiling, and floor, and the angles between them, will affect the range of standing waves in space (a standing wave is a physical phenomenon discovered by Michael Faraday in 1831).

Secondly, the space's acoustics will have a decisive impact on the sound quality. There is debate about how much influence, in percentage terms, the space has compared to the audio system, but there is no doubt that the space's acoustics has a significant impact, so we should do everything we can to improve it.

And here too, the same architectural plan will come to our aid. This way, we can plan the acoustic treatment we can perform in the space, at the environmental level, the envelope, the structural engineering, and the interior design, and all the changes that will improve the quality of the sound in the space, and reduce the intensity of sound pollution to the environment.

To understand how, let’s curate jems from Wikipedia

The biggest challenge that lies ahead is the acoustic room modes at low frequencies. Room modes are resonances that occur in a room when the space is excited by an acoustic source, such as a loudspeaker.

Most rooms have fundamental resonances in the 20 Hz to 200 Hz range, with each frequency related to one or more of the room's dimensions or their division values. These resonances affect the low- to mid-frequency response of the audio system in the space and are among the biggest obstacles to accurate sound reproduction.

How the room resonance mechanism works.

The projection of acoustic energy into a room at modal frequencies and their multiples causes standing waves.

The nodes and antinodes of these standing waves cause the intensity of a particular frequency to vary across space, in response to resonances related to the size of the space.

These standing waves can be thought of as temporary storage of acoustic energy, as they take a finite time to accumulate and to dissipate after the sound source is removed.

Room conditions between two rigid walls.

(Walls must always have a sound pressure junction.)

A room with generally hard surfaces will exhibit high-Q, sharply tuned resonances. Absorbent material can be added to the room to damp such resonances, which dissipate the stored acoustic energy more quickly.

To be effective, a layer of porous, absorbent material must be about a quarter-wavelength thick when placed on a surface; at low frequencies with long wavelengths, this requires very thick absorbers.

Glass fibre, as used for thermal insulation, is very effective, but needs to be very thick (perhaps four to six inches) if the result is not to be a room that sounds unnaturally 'dead' at high frequencies but remains 'boomy' at lower frequencies, so that it provides absorption across a broad range of frequencies. Curtains and carpets are only effective at high frequencies (say, 5 kHz and above).

As a rule of thumb, sound travels at a speed of one-third of a meter per thousandth of a second (344 meters/second), so the wavelength of sounds at a frequency of 1 kHz is about 344 mm, and at 10 kHz, about 34 mm (exactly one-tenth). But even ten centimeters of glass fiber has very little effect at frequencies below 100 Hz, where a quarter wavelength is above 860 mm, so adding absorbent material has almost no effect in the lower sub-bass region at frequencies below 50 Hz, although it can bring a big improvement in the upper bass region above 100 Hz.

How we overcome these obstacles will be discussed in the following posts. This post is about why we need an architectural plan.

Such a plan will give us the ability to adjust the correct specifications in terms of the amplification equipment we will need, but in addition, it will help us understand where the most acoustic energy will accumulate, and therefore will give us the information we need to reduce the detrimental effect that room conditions have on sound quality.

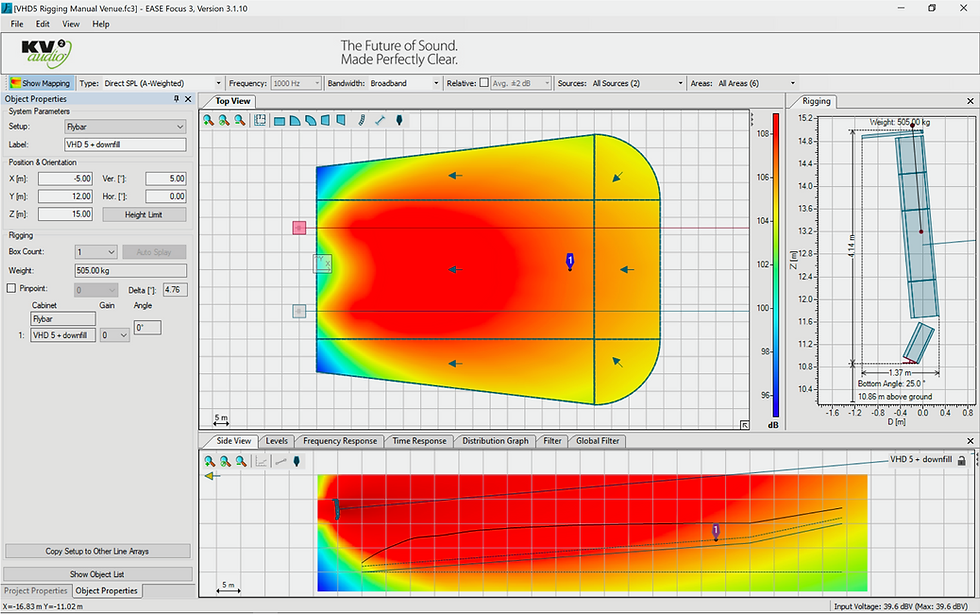

In addition, today it is possible to create a three-dimensional model of the space and, from that, an acoustic model in dedicated software (we rely on the technical department at KV2-Audio, who use EASE). Such an acoustic model can provide the information we need to ensure complete coverage of the space and to accurately assess sound intensity at each point.

It is important to emphasize that our approach is based on the most basic laws of physics rather than complex acoustic calculations, which helps us simplify the process, especially when it comes to actual acoustic treatment.

3D model of acoustic environment

So now that we understand why an acoustic model of space is so important to sound quality, it's important to understand what this model won't tell us: how the sound will actually sound. Yes, we can know with a high degree of certainty what frequencies, and at what intensities each frequency will be heard, but it won't tell us how the sound will actually sound.

By the way, this also applies to audio system specifications. The specification does not tell us how the system will actually sound. It only tells us what discrete data points we have collected about the system - like with the story about the scientists describing an elephant, and each of them describes a different part, so we do not see the big picture.

In our case, it's the same. Power, dynamic range, sensitivity, frequency range, and the like can give us benchmarks, but they won't tell us how the system will actually "sound," because the listening experience cannot be reduced to its individual parts - and yes, I realize that what I'm doing here is exactly the opposite :-) As I'm breaking everything down into pieces and giving you technical benchmarks.

But that's for the reading experience, not for the listening experience.

For the real thing, you'll have to leave the house, which is why I love KV2's quote so much

“We don't measure the performance of our system by specs; we measure it by the smiles on people’s faces.”

That's it for now.

In the next post, we'll learn how to address the club space's acoustic quality based on what we learned from its architectural plan.

Comments